In my defining post, Darktable: crashing into the wall in slow-motion, I presented the trainwreck that the new “Great MIDI turducken” was. The purpose of this turducken1 was to rewrite the keyboard shortcuts system to extend it for MIDI devices.

To this day, I’m still mad about this enterprise of mass-destruction, here is a recap of he the reasons:

- it replaced in 2021 a keyboard shortcuts system that was pretty good, feature-complete, well tested, stable and coded in less than 1500 lines (comments included),

- …to add support for MIDI devices and PlayStation gamepads (!?!)…

- …but in my 2022 Darktable survey, one year after this new feature, over 1251 users who participated:

- 81% of users didn’t have a MIDI device and didn’t plan to get one,

- 2% didn’t even know what a MIDI device was.

- 8% of users had a MIDI device but didn’t use it with Darktable,

- 6% were considering maybe getting a MIDI device in the future,

- 2% of users had a MIDI device they actually used in Darktable,

- the code was absolutely terrible, in terms of:

- code quality: unlegible

if/switch-casestatements nested on 4 levels, in the middle of 1000-lines functions (I posted example snippets in my article), - code volume:

- 3546 lines of code for Darktable 4.0,

- 4397 lines of code for Darktable 5.0,

- the increase in volume is a direct consequence of trying to fix bugs in an architecture that can’t be fixed because its complexity promotes more complexity. All that stems from the design, but solving issues created by complexity with adding more complexity is not a solution.

- code complexity:

- cyclomatic complexity :

- 1088 for Darktable 4.0,

- 1245 for Darktable 5.0 (details ),

- cognitive complexity :

- 1885 for Darktable 4.0,

- 2098 for Darktable 5.0 (details ).

- it is by far the most complex feature of the software, even though it does not operate on images. As a comparison, the second most complex feature is the EXIF metadata decoding, which has a cognitive complexity of 1348.

- cyclomatic complexity :

- code quality: unlegible

- it doesn’t decode key modifiers by design, but only deals with hardware key-strokes, which means:

- “1” input from the numeric pad is decoded

Keypad End, - “1” input from a French AZERTY keyboard is decoded

Shift+&, orShift+"on BÉPO, - you therefore need to duplicate all your number-based shortcuts for each way of entering a number, and be prepared for the shortcut settings window to not contain any actual number in the key combinations.

- “1” input from the numeric pad is decoded

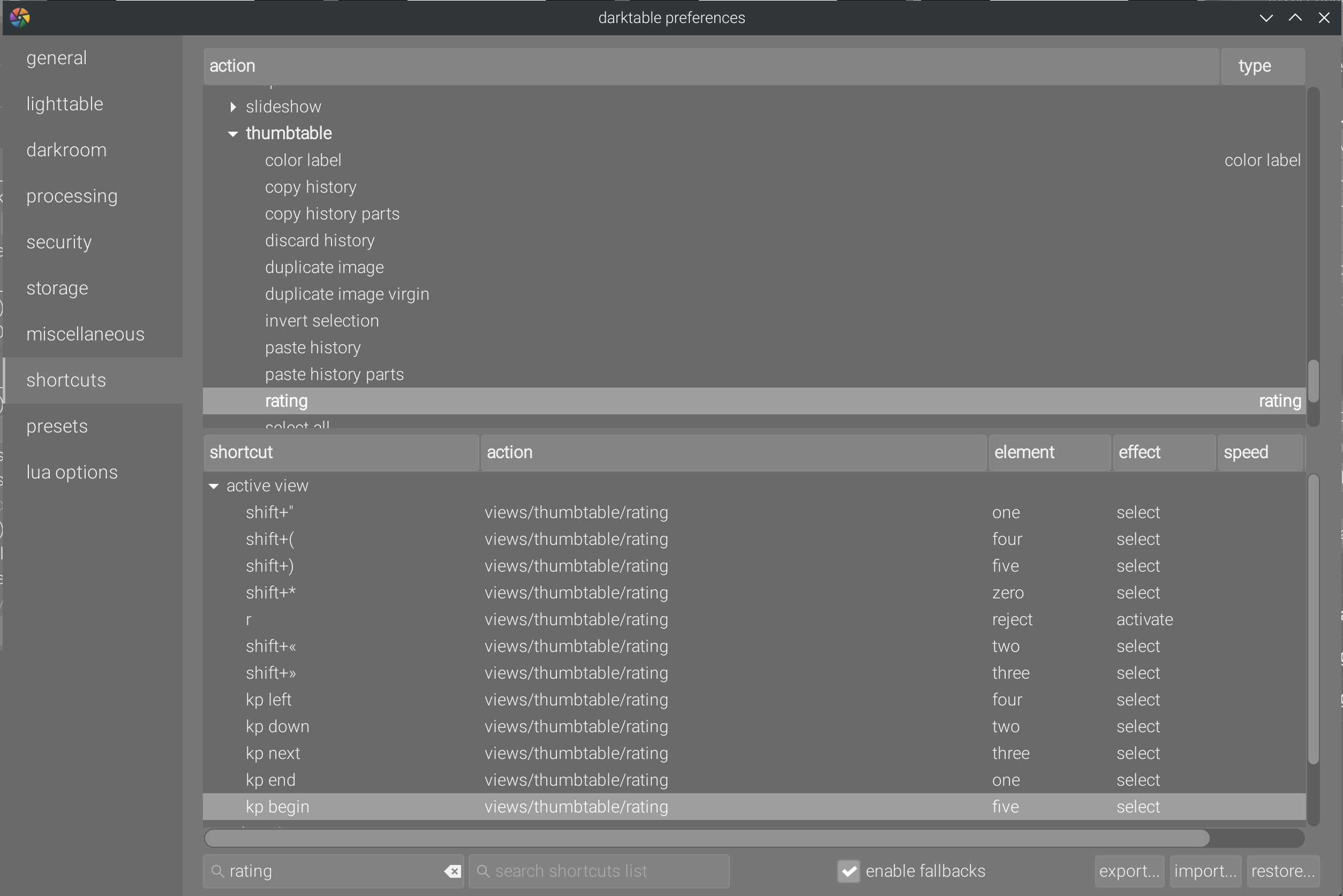

- the user-end design is absolutely terrible, with way too many actions and emulations to configure (“effects”), that are not even fully documented 4 years later (what is “ctrl-toggle” ? “right-activate” ?), and the shortcut configuration uses a weird split-window that doesn’t make any sense,

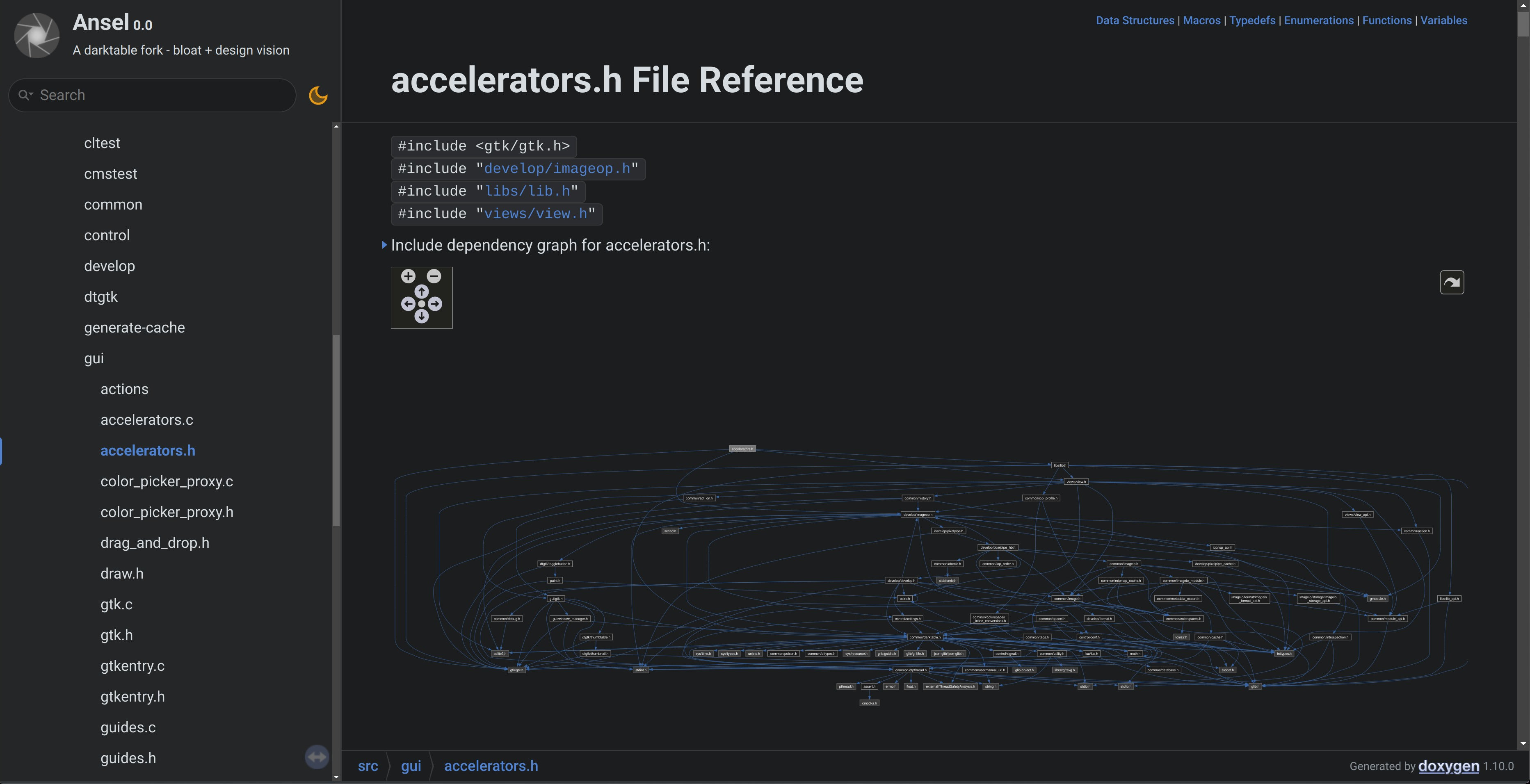

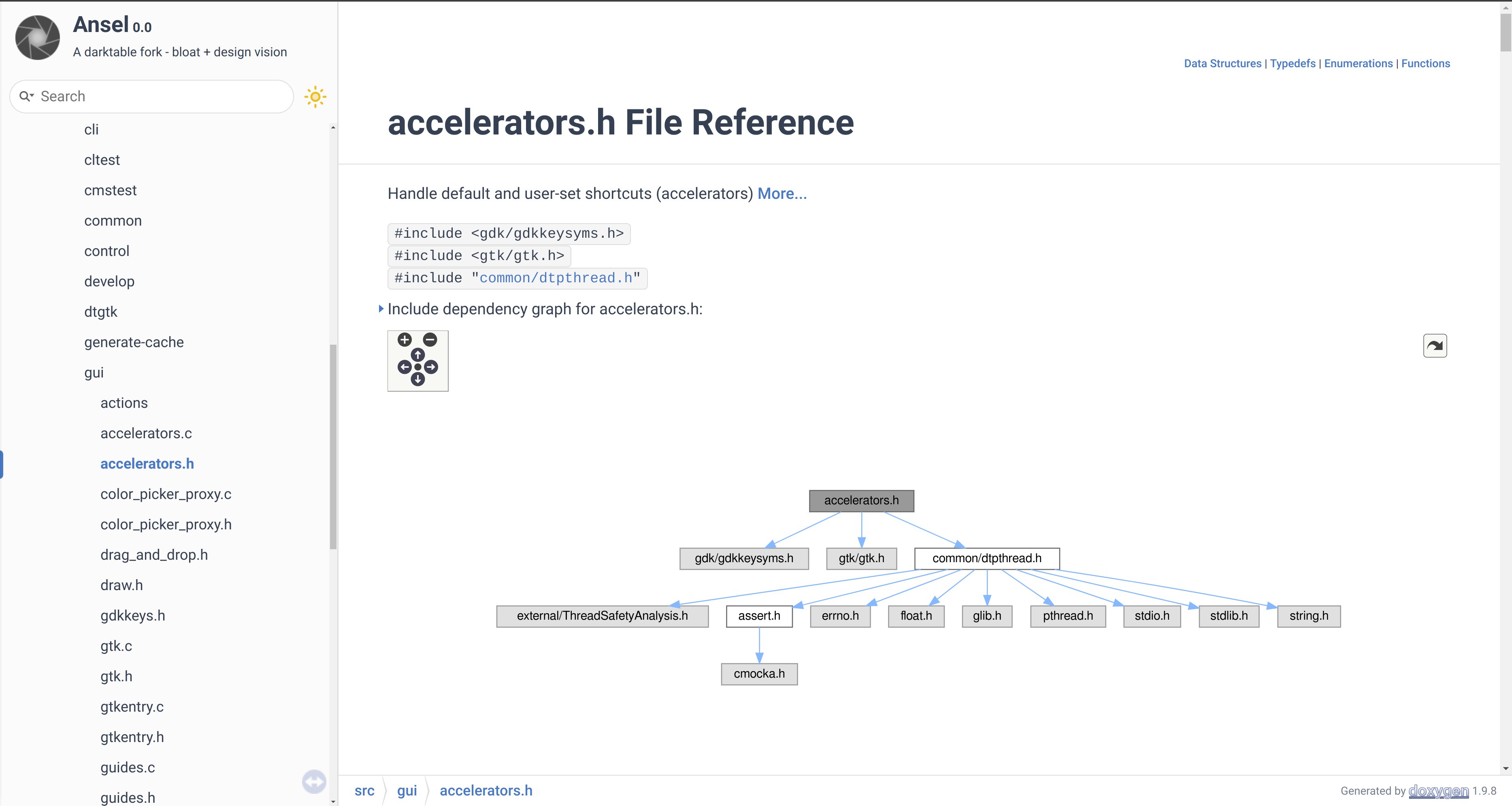

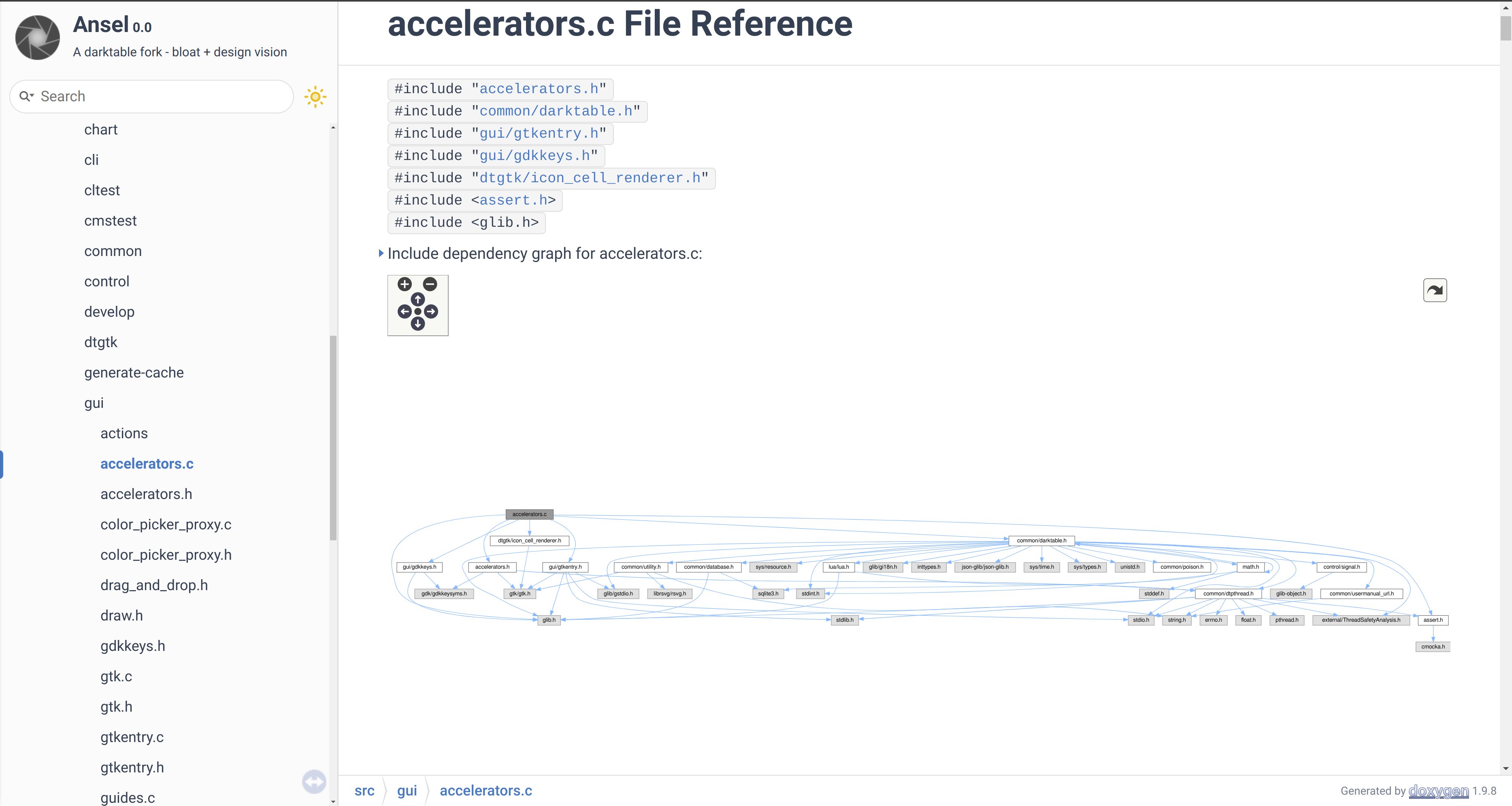

- the implementation is also terrible: the feature is aware of all the software GUI, and the software GUI is aware of the shortcuts code. There is no modularity here, and changing anything in the shortcuts code may have unexpected and undesired effect anywhere in the software.2 Just see the dependency graph below,

- several “shortcuts” (or MIDI bindings) can be attached to the same action, which means every user interaction has to lookup the whole list of available actions, inducing very inefficient shortcut handling, GUI lags in some cases and “unknown key combination” false positives in peculiar cases.

The dependency graph of src/gui/accelerators.c (Great MIDI turducken) before the rewrite. Guess why we call it “spaghetti code "… This makes it clear that there is a double-sided dependency between the accels code and the rest of the GUI code. This is a nightmare to maintain.

So, said otherwise, one (very bad) programmer replaced a working and simple feature by a monstruosity, with the approval of the maintainer (who would never write code that bad himself, but is determined to “not loose momentum” on contributions, whatever the cost), to please 2% of the user base. All that for a secondary (tertiary ?) feature.

I call that wrong priorities. Especially since it took several months of hard work from one developer and many beta-testers, only to make things worse, and then the hard work became a justification to never revert the change, which is known as the fallacy of sunk cost .

I’m an user, I don’t care about code

Caring about the code of the applications you use is just like caring about whether the pipes bringing water to your home are made of lead. It’s not your job, pipes are buried out of sight, so you have all the reasons not to care — and the people in charge of the water network have all the reasons for you not to care — but they will have an effect on your health, and these effects will be unvisible until it’s too late. Software may not have a direct effect on your health,3 but the way it is made will have a long-term impact on you.

I find myself in an uncomfortable position – the Cassandra — having to explain to users that problems they don’t know, don’t see and don’t care about are very much affecting the day-to-day usability and stability of the tools they are using, but in non-obvious ways. In any case, these problems directly affect the probability of any maintainer to, one day, solve the bugs they face.

Bearing bad news makes you the bad news, but bearing bad news nobody cares about makes you an asshole, even though those bad news explain the weird and random issues that get more and more common in Darktable bug trackers since 2021, which don’t get solved over years because at that point, the code doesn’t contain bugs, it is a bug. But here, you have to face filter bubbles : depending on where on the web you look at, you will either find people deeply happy about Darktable (performance, stability, design), and people deeply unhappy about it. My empiric observation is the happy campers, in average, own powerful computers and have STEM degrees.4 The unhappy people tend to move away and reduce the time they loose with the software, which means that, if you are not actively looking for them, you will only feed your survivor bias . And, while I don’t see the point in trying to convert users to Darktable (or to any open-source photo editor), because to each their own, filtering out and deterring users based on their computer-litteracy is a big fail for any photo editing app.

As a guy with a Youtube channel explaining how to use Darktable, and giving 1-on-1 training sessions, I tend to attract more various feedback than only the Github issue trackers (where criticisms of design get shutdown quite fast anyway), and witness first-hand on video chats those weird, random and unreproduceable bugs. Any priviledged guy has a tendency to deny, minimize or disregard testimonies regarding issues he doesn’t face himself, or even blame the issues on the person reporting them. So, I often have this impression of two parallel universes that don’t communicate but look down on each other, when it comes to feedback about Darktable. Of course, Darktable developers chose to look where the sun shines.

And while Darktable looks like an active project with a lot of new features added regularly by a dozen of guys, it’s all the more difficult to explain that what’s actually happening backstage is destruction of the code base, because the code quality is degrading a lot as time goes by, until it will not be possible to debug at all. Volume of changes says nothing about quality, reliability, or maintainability. But 2 centuries of capitalism have conditionned us to seek shiny new features, whatever the cost, and in this regard, Darktable meets the expectations.

Code is born broken. Any software has bugs. Even worse, we use a lot of third-party libraries to avoid “reinventing the wheel”, but those libraries will change their API in the future, meaning code that works today will stop working tomorrow and will need to be reworked in the future, when dependencies change. Code is a like a garden: every new season brings its amount of chores. It is called maintenance. Once this is acknowledged, wisdom is in planning ways to make maintenance possible, first, and then easy.

Good code is code easy to maintain. That is, good code is written in ways that are nice to the people having to read, understand and fix it. We don’t write code for computers. We don’t write code for features to “just work” now and in the next months. Code is not something we hide under a nice hood hoping to never look at it ever again. Code is a living organism that costs energy and time to keep alive.

Maintenance has a cost, one that is often underestimated. It doesn’t matter if your product is the best of the market, if your maintainance costs are prohibitive, (informed) customers will avoid it. Maintenance is boring, uninteresting, not sexy. Maintenance is the opposite of introducing shiny new things: it’s ensuring dusty old things still work quietly. On your software release notes, it goes at the end. Users don’t get excited about maintained features, but they will get mad about unmaintained code and tend to use the wrong metric to assess how well a project is maintained (meaning: agitation and semblance of work). So you will win nothing from maintaining code, but you will loose from not maintaining it, and it will cost you whether you do it or not.

Code is unmaintainable when every bug fix leads to a new bug somewhere else, in a whack a mole way, and the nature of the bug fixes is actually contextual patching and workarounds that only add complexity to the software. When you reach that point, your only option is to rewrite the incriminated code from scratch. Which means that past work has just created more work now. And when that specific past work was already overwritting previous work, we embark in idiocracy.

More code is not a success or an achievement. Achievements are in solving user’s problems. Here again, the capitalistic mindset hits us hard: we would like to measure work by the volume of code added. More code is just more liability, more technical debt, more maintenance costs. That’s a cognitive dissonance since software is precisely about writing code. But think of it like that: making a car is not about adding more steel over 4 wheels, because at some point the car will have to move. You need the right amount of steel, shaped the right way at the right places: you need to be efficient and parsimonious. Software is about solving user’s problems with computers, not about stashing code.

On projects where contributors are not paid, boring maintenance is not where people want to spend their saturdays, and it is a real concern as far as project management goes. It is even more important to make maintainance easy when people work for free. Luckily, Darktable has zero project management, just a hive of random contributors scratching their itch at random times, without unified goal, strategy, schedule or work division. Which is why I would like everybody to stop using the term “Darktable team”. There is no Darktable team, because there is no work division, no leadership, no schedule, no roadmap, no planning, no goal, no priorities, no vision, no strategy, no method, no design, no communication ahead of doing things, no specifications documents for the problems to solve. This is the highschool computer club, made of disconnected individuals.

There are 3 things a developer needs to do to ensure maintenance is as easy as it can be:

- write the least amount of code: tracking a bug among 300 lines will be much faster than among 3000 lines,

- write the most simple code: “simple” as in “the functional logic has few steps, few assumptions, few corner cases”. Simpler means easier to read, understand and fix, but also that there will be fewer cases to cover while testing. In practice, it means avoiding contextual cases, user options, variants,

if/elsein the code. - write self-enclosed code: split the software functionnality between modules (sub-programs) that communicate through the core and are isolated from each other. As the code volume grows, that guarantees that changes happening within modules will not have unforseen effects outside.

Finally, you have to evaluate if the new features you add are worth the extra maintainance cost. In the case of the shortcuts handler, we are catering to the “needs” (or rather, the luxury) of 2% of the user base with an implementation that is at (very) least twice as complicated as the one it replaced. Ponder that in your capitalistic mind…5

Code complexity can be measured using graph theory, through cyclomatic complexity, cognitive complexity, or N-path complexity. Many research articles correlate code volume and/or code complexity to the number of bugs hidden, which is pretty intuitive: the line of code you don’t write is the only one in which you will never have bugs. Simplicity is the goal. And, as I found out the hard way, GUI (front-end) complexity is often a direct consequence of back-end complexity. There are many guys howling at the moon to conjure the mystical figure of the UI/UX designer, hoping to magically solve the terrible GUI of Darktable (complicated and inconsistent). The GUI does not exist in parallel of the back-end, it only wires the input expected by the back-end to graphical controls. Simplifying the front-end cannot be done without simplying the back-end, this is just a stupid dogma made up by people having only soft skills. But simplifying back-ends is a lot more complicated than just drawing mockups.

As it turns out, what happened with the Great MIDI turducken failed on all 3 accounts: code volume, code complexity, code self-enclosedness. And Darktable developers will never learn from their mistakes, as is proven by Darktable 5.0. As keyboard shortcuts bugs piled up over time in Ansel (on top of features terrible by design), I tried to fix them in ways that avoided rewriting the whole thing, until it was pretty clear that I would not be able to avoid the rewrite for much longer.

This is called technical debt . The whole code of the Great MIDI turducken was meant to work once it was written, not to be long-term maintainable. It is basically a proof of concept that should never have made it into production. And the very proof of its unmaintainability is how much the code volume and complexity has grown from bugfix to bugfix, between Darktable 3.8 and 5.0, making it even more unmaintainable as bugs are fixed. This is the definition of gluing yourself into a spider web: the more you move, the more you get stuck.

My mistake is perhaps that I started to raise my critics of the Darktable (lack of) management in 2022, after I got the proof that the disorganized pack of contributors would never recognize and learn from their mistakes. Although the self-inflicted and unsustainable work pace was more akin to create burn-out than reflection. Since then, Pascal Obry, the current self-appointed maintainer of Darktable, has been trying to convince everybody that I’m an unsufferable team member, unable to work with other persons who disagree with me, who started to insult everybody. Of course, no specific and technical answer has been given to the issues I rose in Darktable: crashing into the wall in slow-motion, only vaguely reassuring blanket statements to the tune of “Darktable is an active project, healthy because it has many contributors”. As if more disorganized monkeys would finally equal an engineer if you added enough of them.

I think I have been nothing but nice for 4 years – far too nice, in fact — until I realized how badly these guys harmed the project. They don’t, and will never learn from their mistakes, because they won’t even acknowledge them and the evolution of Darktable 5.0 is only confirming the trend. But having more and more weird, random and unreproduceable bugs pile up on the bug trackers is a pretty clear clue that something is deeply wrong. Especially as investigating those bugs led me to archeology into terrible shitstacks of code that was not even 2 years old, and even though my knowledge and experience on Darktable code base grew over the years, my ability to fix the root cause of bugs decreased and I was facing more and more disconcerting haymazes of code indirections .6

It’s hard to explain all that to people who see computers as magic boxes designed by tech wizards. There is no magic in there. It’s mostly math and applications. Many developers will confess being bad at math, which means they are bad at programming too. Because math is not just about running arithmetic operations, it’s a whole discipline of the mind allowing to abstract complex problems in order to break them into simple problems, that will lead to simple code and simple GUI. Good programmers spend a lot of time thinking about how to write little code. Because code is a liability, code is technical debt, code is costly to maintain. So you pay the debt upfront, without interests, by thinking a lot of your code before you write it, instead of coding first and then spending years extinguishing fires.

All this also raises the question of who owns open-source code and open-source projects. Since the founder of the Darktable project, Hanatos, left the ship, as well as all the first generation of developers, for various reasons, the last standing man from the first generation appointed himself new maintainer. He is a very capable and skilled developer: his code is clean, tidy, and I have not, so far found any bug in a line where git blame said “Pascal Obry”. But his politics regarding code management are terrible: he believes that every contribution is a good contribution, that contribution “momentum” should not be deterred, and is properly incapable of saying “no” to contributions, which means that close to all pull requests get merged. It’s France in 1940: everything comes in, gets welcomed with a big smile and the Führer gets twice as many Jews as requested. Meanwhile, the resistants are called terrorists.

But there is a huge difference between the quality of the code that Pascal writes and the quality of the code he accepts and merges. This is a concerning paradox finding its roots between the fear of missing out and radical techno-positivism , which errs on side of dogma and beliefs, with a complete disregard for design and user perspective. And perhaps and exagerrated trust into the “Community”’s ability to fix bugs later.

There are many cases where doing nothing is better than doing it wrong, especially when you are replacing existing features. Darktable being a non-destructive code editor, you invest into it when you start a database of image edits. Unless you plan on exporting all your images to high-resolution, high-bit-depth files, as soon as you are done editing them, to never change them again. That creates a legitimate expectation of long-term stability and consistency, so your old edits can still be opened, brushed up and exported again, perhaps to new formats, perhaps to higher resolutions. Changing course in the application design is kind of a breach of contract, and even though the GNU/GPL license voids any legal responsibility, it doesn’t void the damages on users. Nor does it refund the years of my life I lost to fix their shit.

So, even disregarding developer-centric issues of maintainance, there is also a discussion to have regarding who gets to decide how old and proven features get replaced, especially those basic and universal desktop applications features like handling files (import, export, browsing) or mouse & keyboard interaction, that have been so ubiquituous for so long that the 2020’s are 30 years too late to pretend reinventing them.

A lot of work and man-hours were invested into making the keyboard shortcuts worse, for the sake of flawed politics and damaging dogmas, on top of whishful thinking and social loafing where everybody hopes that The Community® (aka someone else) will take care of fixing their own mistakes. Users also had to loose their keyboard configuration and were required to reset everything and relearn everything too. But doing it the right way would actually have cost less work and fewer man-hours. This is a self-feeding loop of madness, creating a toxic work environment where instability promotes more instability, where complexity promotes more complexity, again without any sort of features roadmap that would give a general direction and visibility to everybody involved.

A brief history of bad design

It’s only after I reconstructed the shortcuts feature from scratch that I understood what went wrong in Darktable shortcuts/accelerators.

At first, there is this crippling debauchery of features, which makes it tempting to declutter the GUI by simply hiding features, only to have them handled from the keyboard. The problem is then that such features are not always niche and optional (like the shortcut bypassing mask interactions when drag and dropping the main image preview in darkroom), but are definitely undiscoverable from users. Ansel solved this issue with the global menu.

Some features were hidden through a basic vimkeys support, if you start inputting :: :q will quit the application, :set followed by the name of the slider or combobox will change the value. This is of course documented nowhere in the Darktable manual, and as an user of Darktable for more than a decade, I had never heard of it before deleting its code, because this little joke listens to all your keystrokes to determine whether it should act on your typing or not.

But then, there is also the fact that modules use home-made Gtk widgets (named “Bauhaus”, in src/bauhaus/bauhaus.c) that don’t implement everything you would expect from a GUI widget capturing user events, especially not the accessibility features.

One of the most basic accessibility features is the ability to cycle through focusable widgets. In GUI (and Gtk) slang, a focusable widget is one that can capture key stroke events, once focused. Widgets will typically be focused once clicked, but Gtk also manages internally a focus chain into which you navigate with the Tab and the arrow keys. The first problem is the Tab key, in Darktable, was mapped to the “preview” mode (toggle on/off all panels in the view). And in fact, using native Gtk accelerators, this would not have been possible at all, since Tab is mapped by Gtk and forbidden in user-defined shortcuts, but since Darktable implemented its own shortcut handler, even before the Great MIDI turducken, it was overwritten. So, the tabulation-based focusing chain cycling was disabled simply because the Tab key was assigned to something else. But the second problem was that the home-made Bauhaus widgets also captured all arrow key strokes. Thus navigating between controls in a sequential manner (next/previous) was also completely impossible, by design. Just like Bauhaus widgets captured all mouse scrolling events, preventing scrolling the sidepanels.

Because sequential/incremental navigation between focusable widgets was impossible by design, all keyboard interactions had necessarily to be made absolute: for each slider, for each combobox, you would have a shortcut increasing/decreasing/resetting the value mapped directly.

But more problems arose when modules were made multi-instanciable, because controls were identified by an accelerator path like view/module/slider/increase or view/module/slider/decrease, but all module instances would inherit the same path. That triggered a need to manage all that at runtime, with user preferences to decide whether the targetted module would be the first, last or last-interacted-with module.

Generalizing all that to MIDI and gamepads only made it worse, because on top of having one shortcut per possible action per widget, then there was a need to manage typical desktop interaction emulation from other input devices. But instead of managing the emulation layer high-level, at the interface between MIDI and regular keyboard/mouse shortcuts, a terrible developer totally over-engineered an abstraction layer of actions, incrusted into modules, native Gtk widgets (as an overlay), and home-made Bauhaus widgets (deeply incrusted). The problem is that abstraction layer wasn’t really a layer but more like a metastatic tumor spreading everywhere. Removing it and all its dependencies led to the removal of 7674 lines spread over 163 files, even though it was supposed to be implemented in src/gui/accelerators.c (4412 lines of code, comments and whitelines).

Redesigning keyboard shortcuts/accels from scratch

The zeroth-step of the redesign is those 2 simple requirements:

- Every action should be discoverable in the GUI, keyboard shortcuts are not meant to declutter the GUI ; decluttering the GUI is a matter of breaking the workflow into unit steps and presenting only the controls that matter to the current step.

- The software should be completely usable from the mouse alone and from the keyboard alone. Mixed interaction should be completely optional.

The first constraint of the redesign is therefore to make absolute shortcuts completely optional, thas is designing the keyboard workflow for a sequential/relative access (cycling between next/previous control).

Interaction with focused controls

The split paradigm “focus” then “interact” (which I didn’t invent…) is very powerful because it allows to scope key strokes into the right context, which means the same keystrokes (especially the Up/Down/Right/Left arrow keys) can be attached more than once in the GUI, and be handled differently depending on which context has the focus. This is more flexible and actually more simple7 than the Darktable obssession of wiring everything to global, absolute shortcuts which would then collide on often-reused keys, and lead to having to add more and more key modifiers as a work-around.

So far, navigating through controls only gave them focus. What about actual interaction ?

In the lighttable view, once the thumbtable grid is focused, navigation through thumbnails is done using typical arrow keys, Page Up/Down, etc. (see the documentation for all the details) and image selections can be done in various ways (batch, series, individually) from keyboard too.

In the darkroom view, changing values on sliders and comboboxes can be done using the arrow keys (possibly using Shift for coarse step or Ctrl for fine step), triggering the color-picker (on sliders supporting them), is done with Insert, etc. (again, read the doc for details).

So, again, so far no user-defined shortcut, no cryptic key combination to remember, it’s mostly arrow keys and yet everything can be accessed.

Absolute control focusing

That’s all great, but it leaves you on a kind of Ikea trail when you need to access directly some area of the application but you have to navigate through all sections from the entry door.

To alleviate that, a very old Darktable feature was the “favourite modules” tab, aka a special tab that would duplicate the GUI of the most-used modules, based on user choice. That’s essentially solving bloat with more bloat, and yet users have grown very fond of that. Though if we focus on the goal, rather than the mean, the requirement is a quick access to arbitrary modules, which is perfectly understandable.

So this was re-implemented as a way to define an absolute shortcut immediately focusing an image-processing module or any of its internal controls. Focusing an hidden module or control will automatically make it appear in the GUI. From there, further interaction is done exactly as before, using uniform key combinations. This reduces the number of shortcuts to configure by a lot, makes the whole thing more generic and the shortcuts settings window much more simple.

Absolute shortcuts can also target menu entries (aka global actions), in which case they will be recalled in the menu, next to the action label, which is again a native Gtk feature coming with zero overhead.

Replacing MIDI controllers

If we leave aside all the hype of having dedicated controllers and feeling like an airplane pilot, the one thing that MIDI controllers have that keyboard and mouse will never have is the ability to attach potentiometers (rotating knobs) directly to GUI sliders. But then, the cost of that is having an extra device taking space (and dust) on your desktop, not to mention future electronic garbage. All the photographers I know who bought MIDI or Loupedecks stored them away “temporarily” to reclaim some destkop space… and never brought them back from storage.

Image-processing controls can be wired to single-key shortcuts, because Ansel uses a custom shortcuts overlay on top of native Gtk accelerator features. I have modified the home-made Bauhaus widgets such that, when hitting one of the absolute focusing shortcuts above and keeping it pressed, mouse wheel scroll will be directly mapped to the widget even if the mouse is not overlaying the proper slider.

So combining one-letter shortcuts to focus a control, with mouse (or touchpad) scroll, you get all the goodness of MIDI rotating knobs without the extra device, extra library for support and marvels of over-engineered emulation layers.

But all that still happens with the one and single absolute shortcut, so you don’t have to define and remember several shortcuts per control, only to find yourself short of key combinations available.

Shortcut-less actions, search engine and vimkeys-like triggers

My shortcut handler is a thin wrapper over Gtk native accelerators API. As such, an action is defined by a text path, like Ansel/Darkroom/Modules/Exposure/Black level, which is an unique identifier, readable both by a computer and by an human. The GUI declares a function attached to each of these pathes, containing the code to run to apply the corresponding action. Then the shortcut handler maps a key combination to this path.

So, whenever an user hits some keys, the shortcut handler looks up if we have a known path for this combination, and if it finds one, triggers the function attached to it. This is a dummy-proof design that knows nothing about the internal of Ansel modules, home-made widgets, etc. So it can be extended to many parts of the software without overhead.

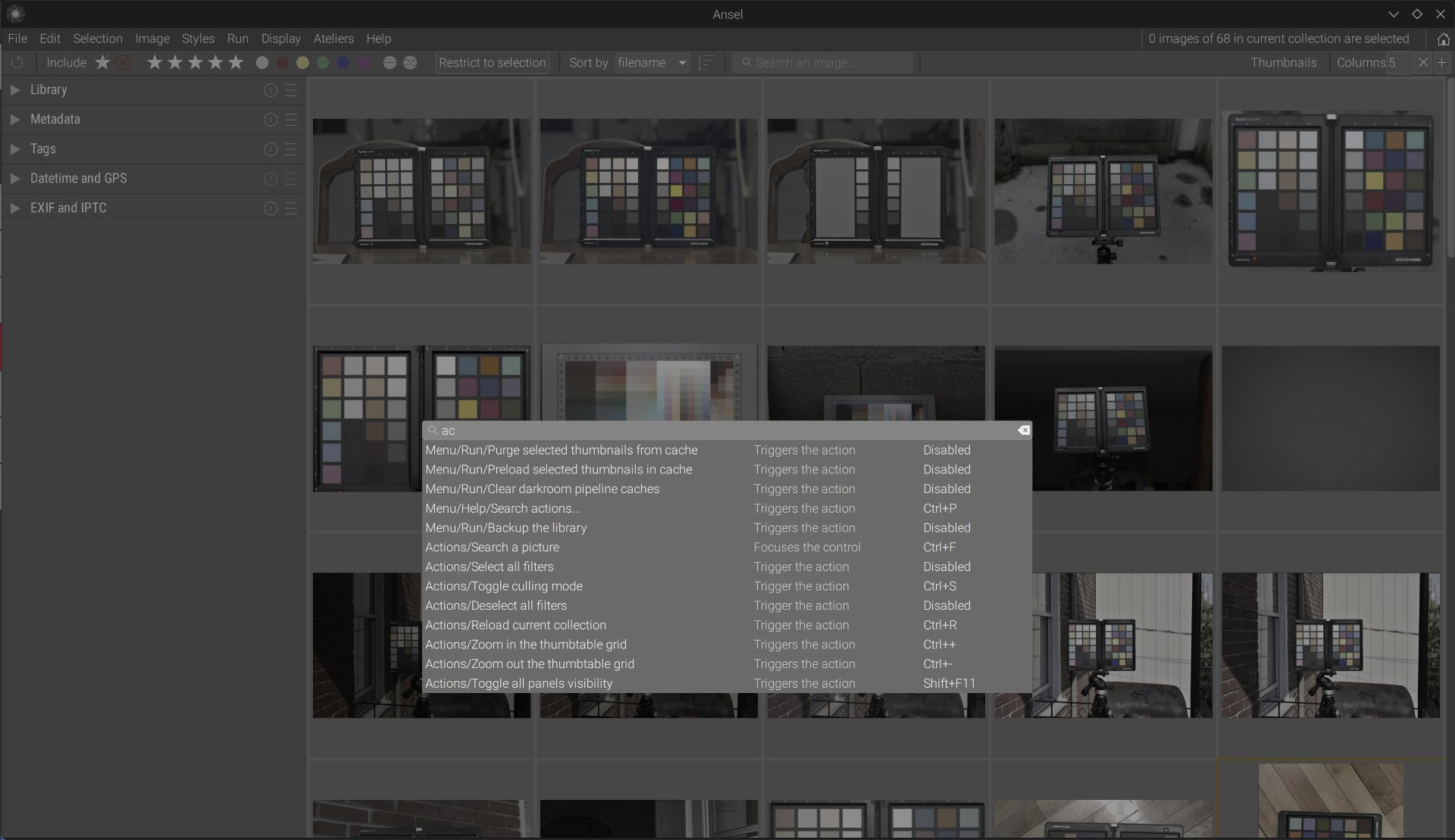

But it’s actually much more powerful than just that. Because by listing all known pathes, we can then return pathes matching a text search query (searching for a control, module or global menu entry by name), that is find all actions from a list, but then we can also trigger them even though they are not attached to any shortcut.

Since image-processing modules can also be found and displayed this way, this also replaces the module search engine, reclaiming some vertical space for long modules and their masking/blending options (and removing around 200 lines of code). From there, I extended it to all toolboxes and made it global, which means the action search engine works in all views but will only list the actions relevant to the current view.

In darkroom, it also supports module multi-instances, allowing to target directly a specific instance (more on that on the documentation).

By default, the global action search is mapped to the Ctrl+P shortcut, and can be accessed from the global menu Help, or with a Search actions button in the center of the header bar. This also somewhat replaces the vimkeys that had a very partial support of GUI actions (and would have needed to entirely duplicate accelerators to extend it to an useful state), such that, instead of typing : followed by a command, you can type Ctrl+P and either type the path of the action, or start a query and pick from the list of matches (using arrow keys and then Enter).

Matches are sorted by decreasing relevance (top to bottom), and relevance is computed from the position of the match. The assumption here is that, action pathes being generic to specific from left to right (view/module/control), text matches happening on the end of the path are supposed to match controls rather than modules or views, which we consider to be more specific and therefore more relevant. This may avoid having to scroll down past all modules content that could match a text query searching for a control.

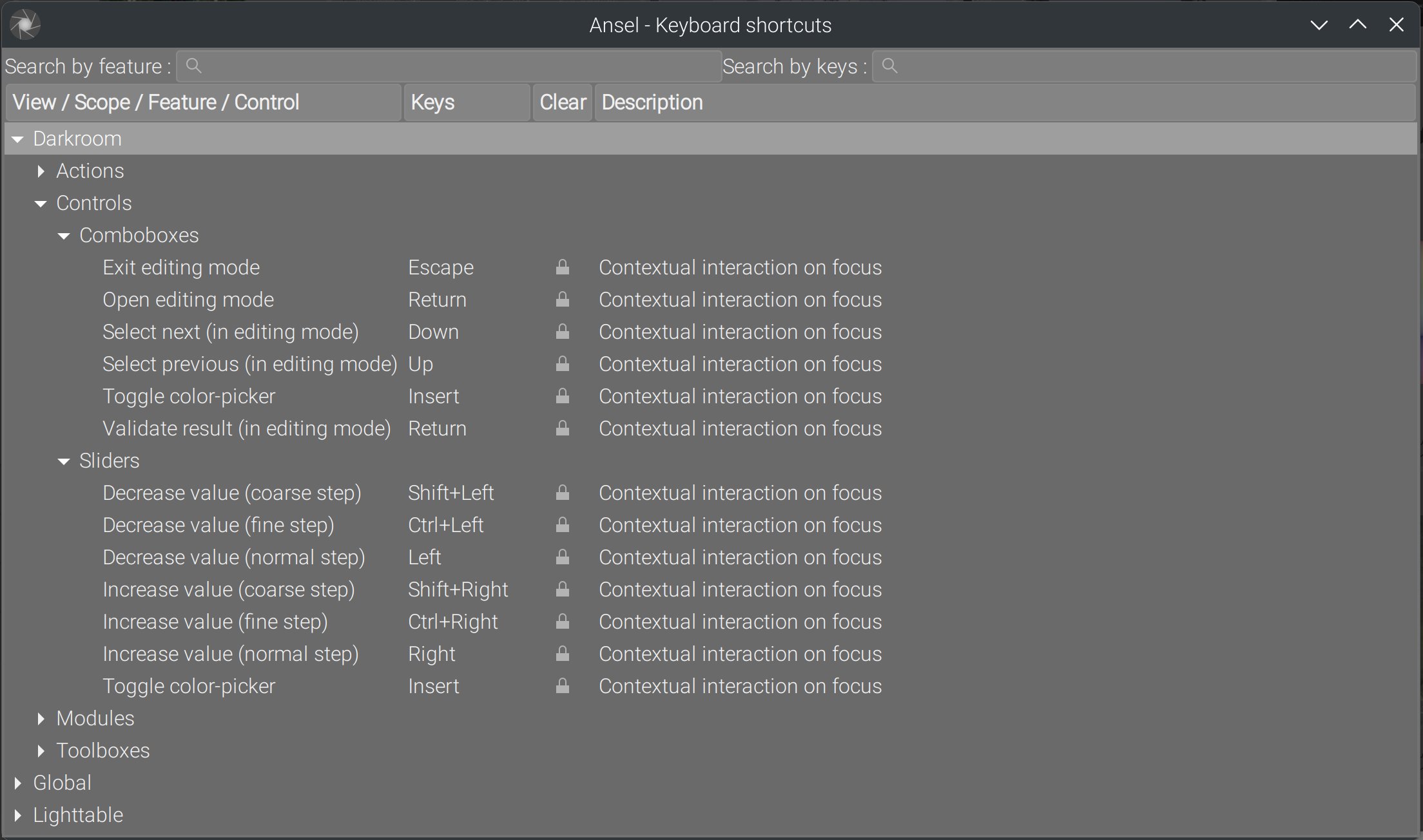

Shortcuts editing window

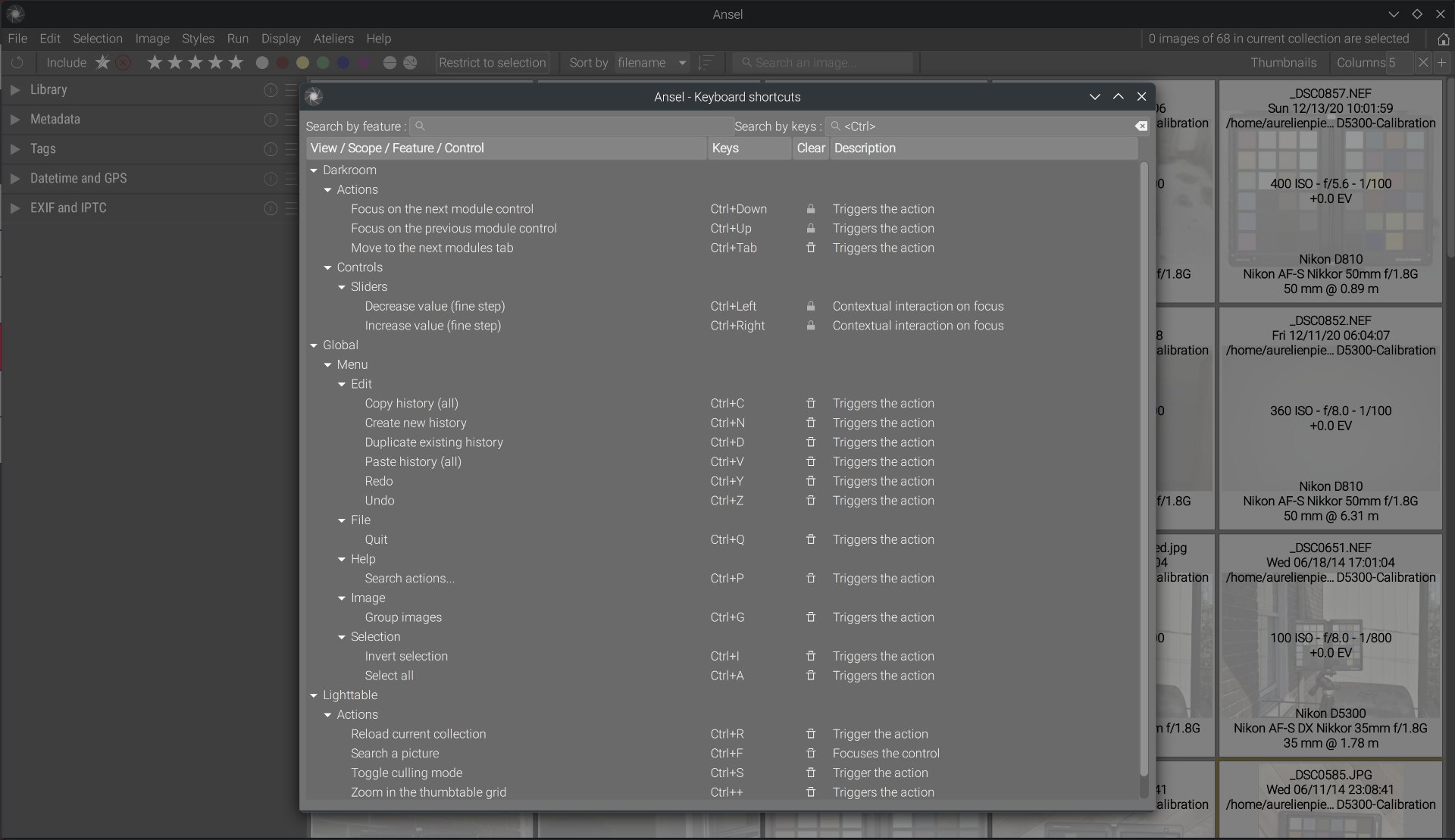

Since there is now only one user-configurable shortcut per control, the GUI for listing and editing shortcuts is a simple tree:

Suffice to double-click in the Keys column to start recording a new key combination. Since it is so simple, this window also replaces the cheatsheet all at once. Shortcuts can be looked up by name of the action or by keys used, and the key search has auto-completion for key modifiers (details in the documentation). The shortcuts popup can be displayed from the global menu Edit → Keyboard shortcuts…

In-software documentation

Here is the thing: maintaining an up-to-date documentation on default shortcuts is an hassle, because it’s too fine-grained. This is the kind of document that will be outdated by the time you finish writing it. Since default shortcuts have to be implemented in the application anyway, the best place to document them is straight within, so updating is automatic.

Darktable had 2 redundant shortcuts GUI, one to setup shortcuts, and another “cheatsheet” kind of popup (which, for a long time, was accessible only through… a shortcut. So much for discoverability). The reason was that the settings popup was way too cluttered to be used as any kind of quick reminder. Then, shortcuts were added in the tooltips of some controls… tooltips appearing only when hovering the controls with the mouse. How non-sensical is it that you should use your mouse to discover how to use the keyboard on a case-by-case basis ?

Ansel has shortcuts (key combinations) written in the settings popup, and also recalled on the global action search. But those shortcuts are not limited to the ones that are user-configurable, I extended the shortcuts handler with “virtual shortcuts”, that is shortcuts basically mapped to no action but declared just like the rest, and appearing among the rest as “locked” shortcuts.

Those shortcuts described as contextual interaction on focus document the generic actions targeting the focused control, whether the control was focused in a relative or absolute way.

Implementation details

The source code for the whole shortcuts handler system, including the GUI bits (global actions search and shortcut editing popup), uses 1144 lines of code, half of them being the GUI, for a cyclomatic complexity of 216 . That’s a fifth of the code volume for a sixth of the complexity (compared to Darktable 5.0), even though it provides additional features (keys search with auto-completion, global search, explicit module instances targets, etc.). MIDI support has been dropped because, quite frankly, I don’t see what problem it solves that is not already solved by the current simpler design.

Finding the action attached to a key stroke takes around a dozen of nanoseconds, where the Great MIDI turducken took 10 to 50 milliseconds on each stroke.8

The dependency graph of the feature can be seen on the developer documentation, it is much cleaner than the previous spaghetti bowl. The rest of Ansel GUI code interacts with the shortcuts handler by declaring new accelerator pathes, recording callback functions attached to them, and possibly default shortcuts, all that using a single method from the API. The shortcuts handling is unaware and immune to Ansel internals, in particular it doesn’t know anything about modules or home-made Bauhaus widgets, so the design is entirely self-enclosed. Preferences are stored per-language in ~/.config/ansel/keyboardrc-LANG, using a native Gtk accelerators map . The API is fully documented on Ansel developer documentation for future maintainance and extension, so no reverse-engineering will be needed.

This is how I work because I don’t program for fun. I have no fun programming. I solve problems, trying not to create new ones.

Conclusion

This is the poster case of everything that went wrong in Darktable in terms of relentless over-engineering and how it should have been fixed. The proposed solution here is better because:

- the whole GUI can be navigated from keyboard without having to remember a single shortcut,

- controls, modules and other actions have only one direct, absolute user-configurable shorcut, that directly triggers the action or focuses the control widget if any, which makes the settings GUI a lot less overwhelming and removes the need for an additional cheatsheet popup,

- actions are globally searchable and triggerable, whether or not they are tied to a combination of keys,

- Key+scroll mixed interactions can be triggered at no additional cost, emulating MIDI rotating knobs and sliders with no need for extra hardware,

- The code is objectively 5 to 6 times simpler (depending on which metric you consider),

- The whole thing is fully documented and heavily commented in the code,

- Any future brain-dead idiot able to read C will be able to maintain this thing, which anyway shouldn’t need much maintainance because it does nothing clever and lives outside of the core of the software.

Translated from English by : Automatically generated. In case of conflict, inconsistency or error, the English version shall prevail.

A turducken is a chicken stuffing a duck stuffing a turkey. That’s a decadent amount of meat that will likely go to waste, unless you have 20 persons to feed. Anyway, it will take forever to cook, and the turkey will likely be dry by the time the chicken is well done. ↩︎

Developers call that “whack-a-mole bug fixing” . ↩︎

Although the stress and anxiety inflicted upon workers by ever-changing software stacks is largely underrated, since innovation is deemed to increase productivity by definition, regardless of user feedback. ↩︎

STEM: Science Technology Engineering Mathematics ↩︎

I don’t see why the capitalistic mindset is ok when it comes to getting excited about new products, but gets boring when it reaches return on investment and hidden/sunk costs… ↩︎

I’m not talking here about the Darktable way of “fixing bugs” that consists into rushing on the visible manifestation of the bug, and adding a fourth level of nested

ifto take care of the pathological corner case. That’s working around the cause of the bug by creating more technical debt, not actually fixing the root cause of the bug. And since that root cause will generally stem many visible manifestations, patching all the manifestations is actually more complicated on the long run, and leads to brittle code. ↩︎Flexibility is usually the opposite of simplicity, so you have to enjoy when you can win on both fronts. ↩︎

Remember that the shortcut handler has to listen to all keystrokes before deciding if it’s supposed to do something with them or discard them, so this part of the software runs all the time for all users, whether or not they actually use shortcuts. ↩︎